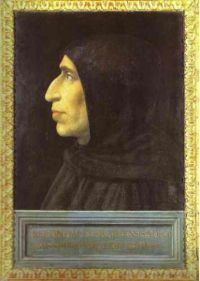

Savonarola

From The Cambridge Biographical Dictionary:

Savonarola was an Italian religious and political reformer, born of a noble family in Ferrara. In 1474 he entered the Domican order at Bologna. He seems to have preached in 1482 in Florence; but his first trial was a failure. In a convent at Brescia his zeal won attention, and in 1489 he was recalled to Florence. His second appearance in the pulpit of San Marco — on the sinfulness and apostasy of the time — was a great popular triumph; and by some he was hailed as an inspired prophet.Under Lorenzo de'Medici, the Magnificent art and literature had felt the humanist revival of the 15th century, whose spirit was utterly at variance with Savonarola's conception of spirituality and Christian morality. To the adherents of the Medici therefore, Savonarola early became an object of suspicion, but until the death of Lorenzo (1492) his relations with the church were at least not antagonistic; and when, in 1493, a reform of the Dominican order in Tuscany was proposed under his auspices, it was approved by the pope, and Savonarola was named the first vicar-general.

But now his preaching began to point plainly to a political revolution as the divinely ordained means for the regeneration of religion and morality, and he predicted the advent of the French under Charles VIII whom he soon afterwards welcomed to Florence. Soon, however, the French were compelled to leave Florence, and a republic was established, oif which Savonarola became the guiding spirit, his party ("the Weepers") being completely in the ascendant. Now the puritan of Catholicism displayed to the full his extraordinary genius and the extravagance of his theories. The republic of Florence was to be a Christian commonwealth, of which God was the sole sovereign, and His Gospel the law; the most stringent enactments were made for the repression of vice and frivolity; gambling was prohibited; the vanities of dress were restrained by sumptuary laws. Even the vainest flocked to the public square to fling down their costliest ornaments, and Savonarola's followers made a huge "bonfire of the vanities."

Meanwhile his rigorism and his claim to the gift of prophecy led to his being cited in 1495 to answer a charge of heresy in Rome, and on his failing to appear he was forbidden to preach. Savonarola disregarded the order, but his difficulties at home increased. The new system proved impracticable and although the conspiracy for the recall of the Medici failed, and five of the conspirators were executed, this very rigour hastened the reaction. In 1497 came a sentence of excommunication from Rome; and thus precluded from administering the sacred offices, Savonarola zealously tended the sick monks during the plague. A second "bonfire of vanities" in 1498 led to riots; and at the new elections the Medici party came into power. Savonarola was again ordered to desist from preaching, and was fiercely denounced by a Franciscan preacher, Francesco da Puglia. Dominicans and Franciscans appealed to the interposition of divine providence by the ordeal of fire. But when the trial was to have come off (April 1498) difficulties and debates arose, destroying Savonarola's prestige and producing a complete revulsion of public feeling. He was brought to trial for falsely claiming to have seen visions and uttered prophecies, for religious error, and for sedition. Under torture he made avowals which he afterwards withdrew. He was declared guilty and the sentence was confirmed by Rome. On May 23, 1498 this extraordinary man and two Domican disciples were hanged and burned, still professing their adherence to the Catholic Church. In morals and religion, not in theology, Savonarola may be regarded as a forerunner of the Reformation. [1]

References

- ↑ Magnusson, Magnus, KBE, Cambridge Biographical Dictionary, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 1300